This Tom Hanks horror-satire is basically a compendium of middle class white fragility, which is the engine of the suspense as well as the humor.

This Tom Hanks horror-satire is basically a compendium of middle class white fragility, which is the engine of the suspense as well as the humor.

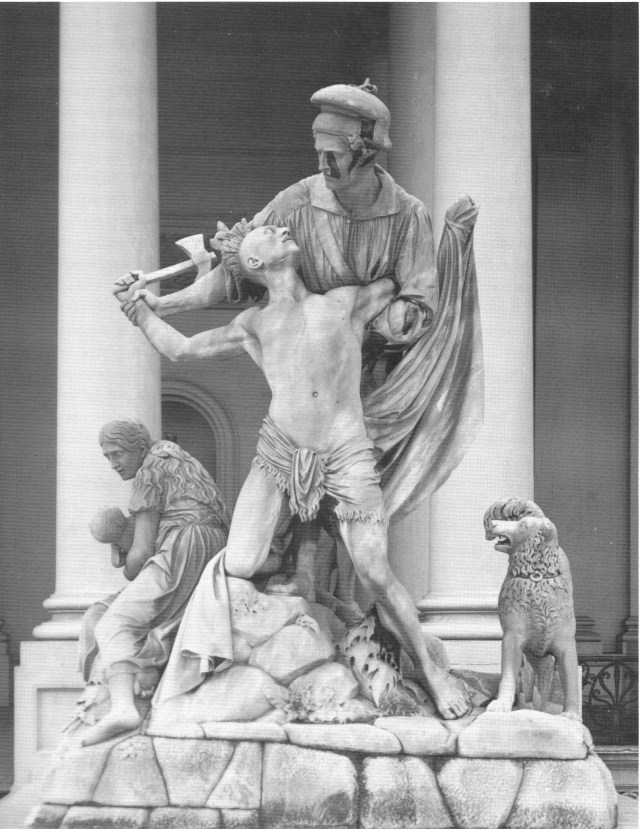

History is a pile of bones, and even if offensive, should perhaps provoke us and shake us from the amnestic waters of late capitalism, which by its own design wishes to maintain the façade of reason, order, and omnipotence making us all feel the helpless consumerist torpor. Shoppers don’t want to be bothered by statues of Puritans restraining the mohawked red menace. It’s a historical fissure breaking through the postmodern simulacrum revealing the truth of our world. Racist statues pierce the veil of McWorld, exposing its menace. One cannot understand the history of his nation without understanding that its history can be measured in red, brown and black bodies. Both in flesh and wood.

At the same time it leaves open the question that perhaps we ourselves are not the bastions of enlightenment that we think we are, but are much the product of our cultural time. I suspect every generation believes that they are the ones who have it all figured out. Until they start to be replaced by a new generation and start to long for the good old days. But the acceptance of this mutability and ambiguity leaves open the consciousness possible directions for the future striving for the wokeness of self-knowledge. A future in which, inevitably, future generations will look back at us as prisoners of this time and see us for the barbarians we are.

I’m perplexed by the slew of negative reactions. Downsizing, although not a perfectly polished film like his 2005 masterpiece Sideways, is without a doubt Payne’s most ambitious and thoughtful political and social satire. I’ll explain why this is a great film – a twenty-first century Gulliver’s Travels.

But despite its flaws has an underlying structure that could have made for a great film. As time goes on, I’m beginning to realize a couple of things about Costner’s disaster epic. One, that it was perhaps an ill-timed film – perhaps made a decade too late or two decades too soon. And in the critical flaws of the film’s tone, particularly in the much dissed second half, could be much better interpreted in the real life dystopian Trumpian America of 2017.

The following presents further where the character form of the American vigilante hero in our cultural imagination, in film, folklore and in real life, is treated as a kind of convenient danger. An angel to some, a demon to others, living in the edges of society where the moral grey areas of the American frontier still exist, where the man of violence waits for another crisis to put his discomfiting skills to use.

The Geist, the specter, of Tyler Durden, fueled by the restless spirit of the office park dystopia, is a force personifying much of the malcontents in this age of anger. It’s interesting to place Fight Club not as fiction, but as prophetic documentary evidence of a time and place, a metaphor of the historical present, a world trapped between McWorld and Jihad, between globalism and it’s blowback.

If the simulation of empire is broken – what sort of blowback might be a fitting comeuppance from these Frankenstein’d gunslingsers from Frontierland? What sort of robojihad might they wage against McWorld’s future technotopia? What other vengences, what other of hell’s gates from the depths of history might be woken once simulation’s zero death game is betrayed?